In the 1970s when Joni Mitchell crooned “Big Yellow Taxi”, not many realised the clairvoyance and the forewarning that the song’s lyrics expressed. Though every bit of the lyric has its own essence and social messaging, the starting couplet is resounding. The verse—“They paved paradise, And put up a parking lot”—held a mirror up to society, and here we are four decades later, perplexed and baffled as to how we got here.

Automobiles are the scourge that drive up emission levels and other environmental issues, yet their numbers continue to rise unabashed. As per a report by the Centre for Science and Environment (Delhi), it took India 60 years (1951-2008) to cross the mark of 105 million registered vehicles. The same number of vehicles were added in a mere six years (2009 – 2015) thereafter!

But when you throw ill-conceived parking systems into this mix, it is like taking gasoline to a firefight. The backlash of this self-inflicted problem is found in every nook and corner of our cities, in all sorts of positions (angular, parallel, perpendicular) and scales (on-street, multi-level, automated).

In India, the conversation surrounding parking management is kindled every now and then, only to be impounded with plans of creating more parking spaces. Or even worse, buried six-foot deep with a parking lot as a symbolical headstone. Irony at its best.

So, why is it that dialogues on parking and its management generate public ire, whereas implausible measures—such as unchecked on-street free parking and multi-level parking—venerated. The answer lies in the psyche of vehicle owners and commuters in general, who lay fodder to a whole bunch of myths regarding parking management.

Now, what are these myths and how do the arguments hold; well, not as solid as the ground their vehicles are parked on.

Let’s deduce this argument with the adage, “Your liberty to swing your fist ends just where my nose begins”. A citizen has the liberty to own a vehicle, but it doesn’t entitle them to occupy a public space of their fancy. Furthermore, no text, context, and subtext of a right allows for the infringement of someone else’s right. Whereas, parking poses as an obstruction for someone to use that common public space from walking or cycling.

Clearly, parking is not a right or an entitlement, but a privilege which needs to be charged and heavily at that. A parking fee must be charged proportional to demand, factoring in criteria such as location, time of day, duration of parking, and category of vehicle (defined by size and type).

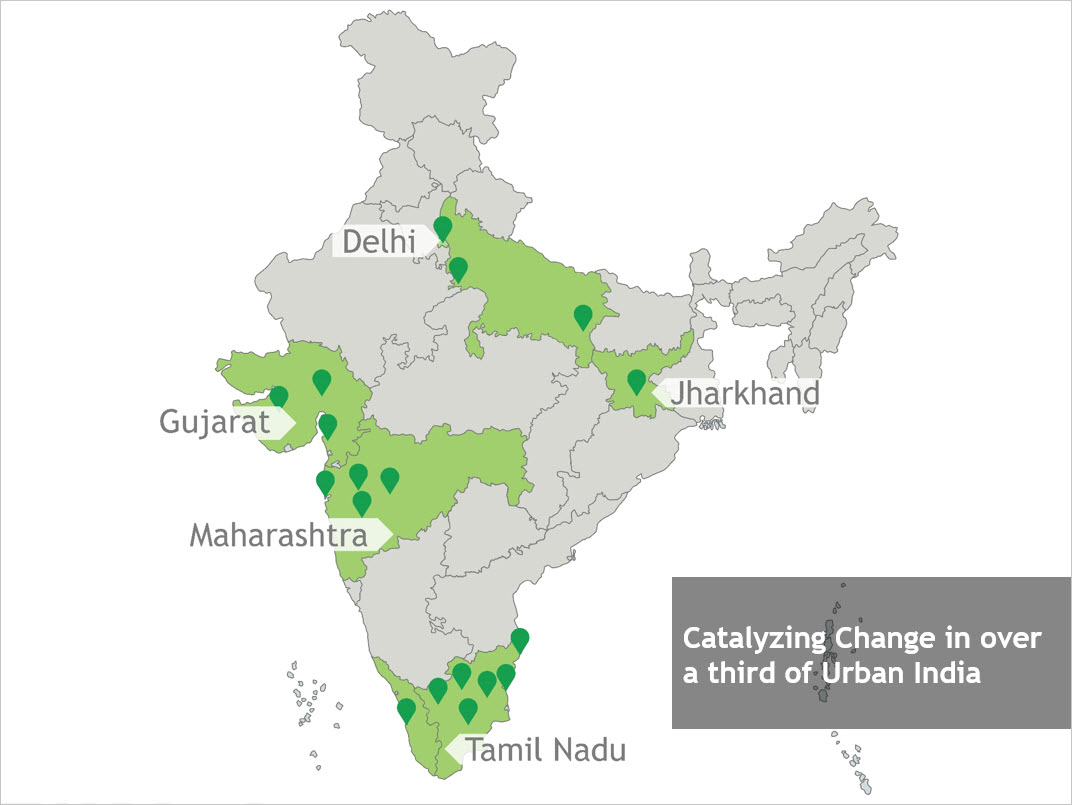

Take the case of Ranchi, where a pilot parking management project on the arterial MG Road stretch led to a 12-fold increase in parking revenue. Even the state of Jharkhand, spurred by the revenue spike at Ranchi’s pilot parking management project, invested efforts to regulate parking as a statewide policy. According to reports, Greater Chennai Corporation stands to gain Rs 55 crore per year in revenue from the pricing of about 12,000 ECS (equivalent car spaces) of parking in Chennai: a whopping 110 times increase in revenue from what it presently earns.

Cities can innovatively use parking revenue to encourage sustainable modes of transport. For example, Bicing—the public cycle-sharing program in Barcelona—is financed by its parking revenue. London’s Freedom Pass, which allows elderly (60+) and disabled residents to use public transport for free, is funded by the parking fees collected in many boroughs. You can find more about these cases and other best practices in ITDP’s publication, Europe’s Parking U-Turn: From Accommodation to Regulation.

As per Dalia Research, the average global commute time per workday is 1 hour 9 minutes, India’s commute estimate hovers around 1 hour 31 minutes. That figure helps us to the third spot in the global list, behind only Israel and the UAE. So does the solution of offering more parking space offer a concession on congestion, the answer is and has always been in the negative.

An analogy often used while talking about urban commute is “Travel time was so much lesser when there were lesser vehicle!”. Hence, parking is to private vehicles, what flame is to moths. More parking only begets more private vehicles to hit the road.

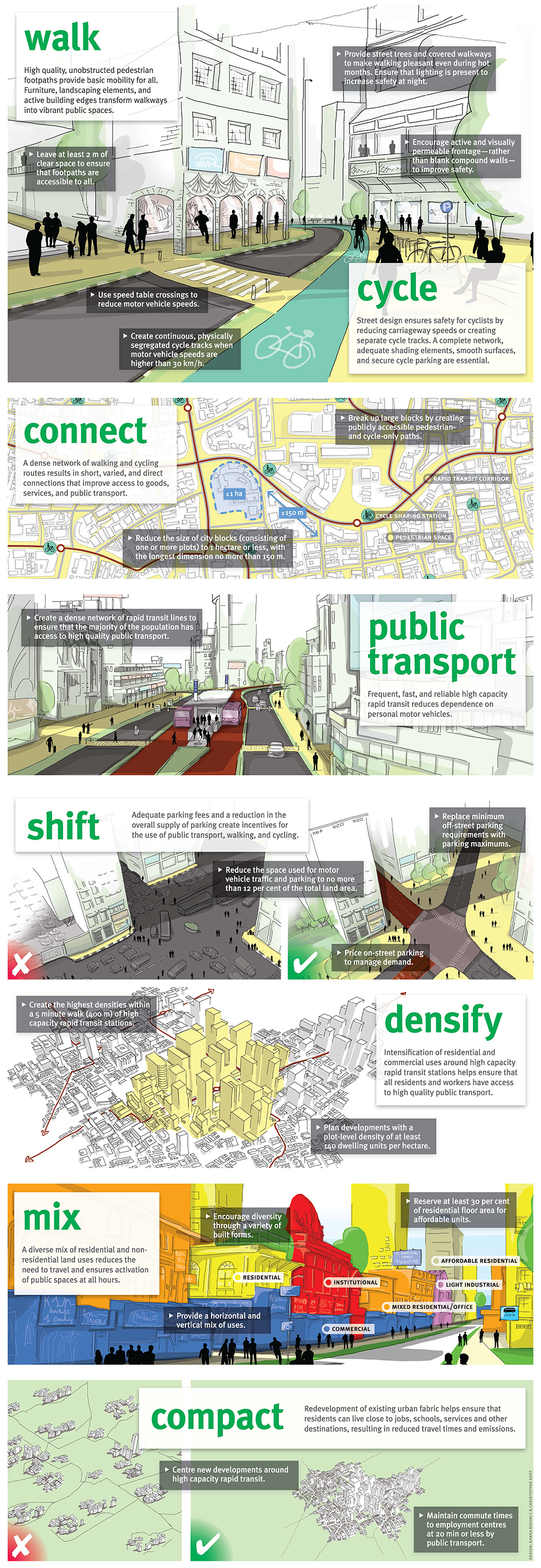

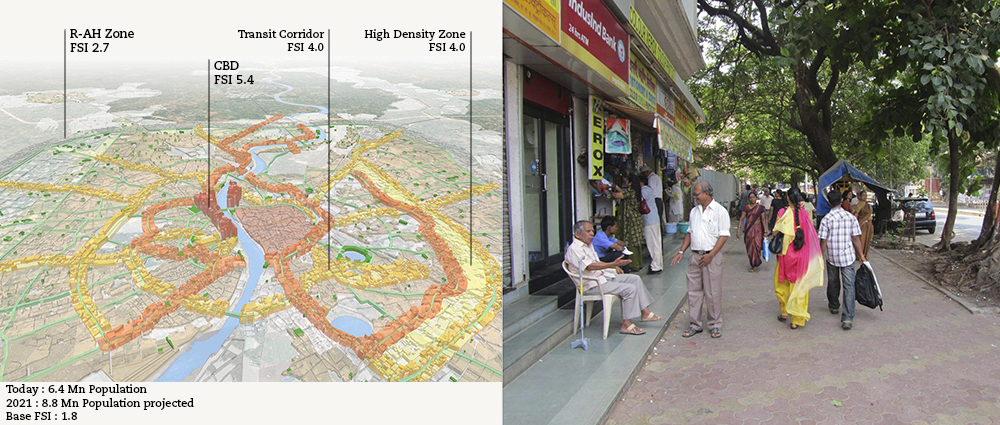

An excessive supply of parking will only encourage people to use personal motor vehicles—even when good public transport is available. Cities, therefore, need to limit total parking supply, including off-street and on-street parking. Based on the capacity of the road network, cities must set caps on the total quantum of parking available in each zone.

Most cities invest in developing multi-level car parks to resolve parking woes. But examples, from across the world and India, clearly indicate that it is a myopic attempt. Over time such infrastructures only turn into ‘big white elephants’.

Take the example of Bengaluru’s 11 multi-storeyed parking complexes—Bengaluru Metropolitan Transport Company (BMTC) owns nine and the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) owns two. According to a Bangalore Mirror report, these “ghost storey” parking lots barely have 20-30% occupancy, reason being parking on roads or pavements is easier, since it is free and the safer.

“Multi-level car parking doesn’t solve parking woes, better on-street management does. Multi-level parking structures remain empty while people continue to park on the streets as long as it remains free and unenforced,” said Shreya Gadepalli, ITDP India Programme Lead. Thus, cities must manage and enforce on-street parking effectively before building any off-street parking facilities, public, or private.

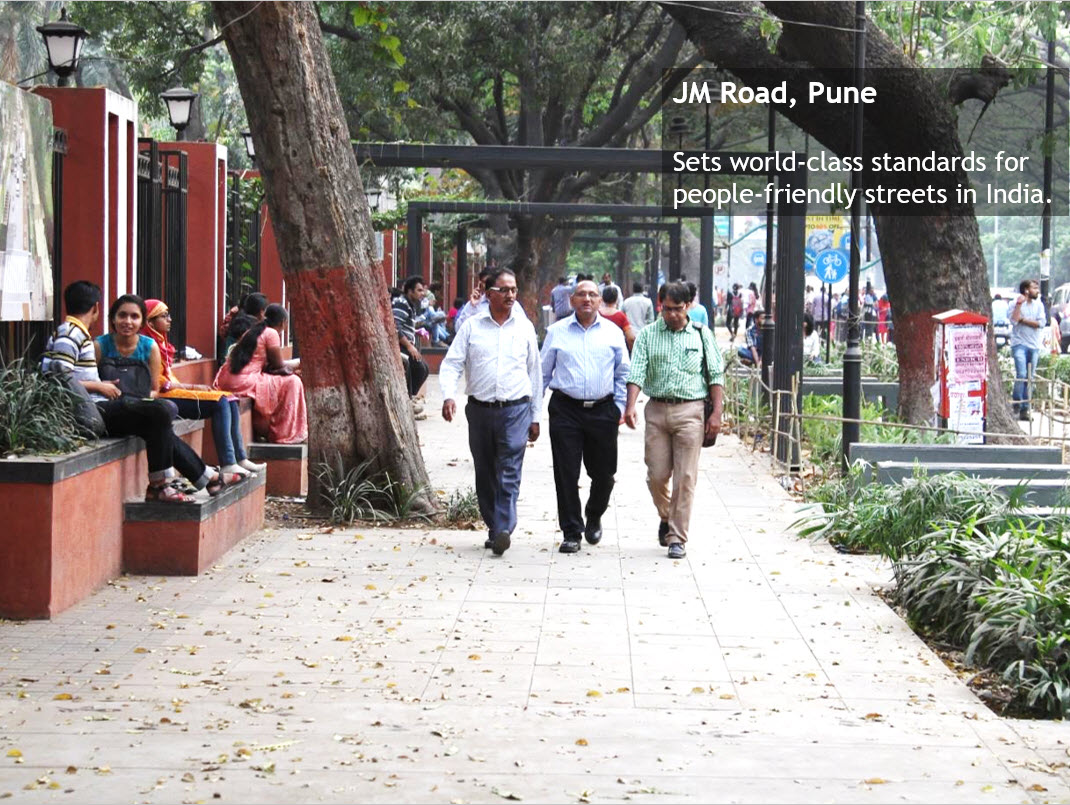

In 2009, Janette Sadik-Khan, the then transportation commissioner of New York City, envisioned Times Square to be a car-free zone. That is, the hub would be less of a conduit for vehicles and an urban space where people could freely walk, sightsee, dine, and take in the magnanimity that is New York. Though there were initial reservations, the results were quite remarkable and by 2010 the changes were made permanent. Citylab reported that “business for merchants in the area was booming, and travel times for cars actually went down”.

There are plenty of such examples be it Hong Kong—where demand for commercial establishments rose post pedestrianisation, Copenhagen—a pilot pedestrian project from 1962 has since reclaimed 100,000 sq.m of motorised transit. Here in India, the Mall Road in Shimla, Temple Street in Madurai, and Heritage Street in Amritsar are examples of how reinventing urban design to focus on pedestrianisation does not affect commercial establishment as feared.

People over parking: regulations allows better streets, better cities, better lives

In conclusion, the need of the hour is to regulate parking, not to take it off the table. Policies which focus on parking management not only help in easing congestion, emissions, and travel time, but also are a feasible revenue generation model for a city. A robust management system clearly defines parking zones, pegs user fee to demand, and uses an IT-based mechanism for information, payment, and enforcement—discussed at length in ITDP’s Parking Basics.

The conversation revolving around parking management has been catching up, with ITDP India Programme offering plausible solutions to cities. Leading the conversation is Pune, which is on the verge of implementing a parking management policy—a demand-based parking system that smoothens traffic movement.

Multiple studies allude that personal cars and two-wheelers occupy most of our street space, yet serve less than a fourth of all trips. They also sit idle for 95 per cent of the time—consuming over a third of street space that could be used more effectively as footpaths, cycle tracks, and bus rapid transit (BRT). The discourse over urban mobility shouldn’t revolve around parking, rather the onus must be on transit-oriented development. Wherein, last-mile connectivity and rapid system of transit ensure movement of people and not just vehicles. As cities evolve, there is an urgent need to step away from an oblivious “man proposes and parking disposes” mentality.

More resources from ITDP on parking management and reforms:

InFocus: Revolutionary Parking Reforms

India’s first car-free Sunday in Ahmedabad in 2012

India’s first car-free Sunday in Ahmedabad in 2012 People enjoying hop-scotch at the car-free Sunday in Coimbatore

People enjoying hop-scotch at the car-free Sunday in Coimbatore Father and daughter bonding over skipping at the car-free Sunday in Chenani

Father and daughter bonding over skipping at the car-free Sunday in Chenani

Consultation with Nashik Municipal Corporation

Consultation with Nashik Municipal Corporation