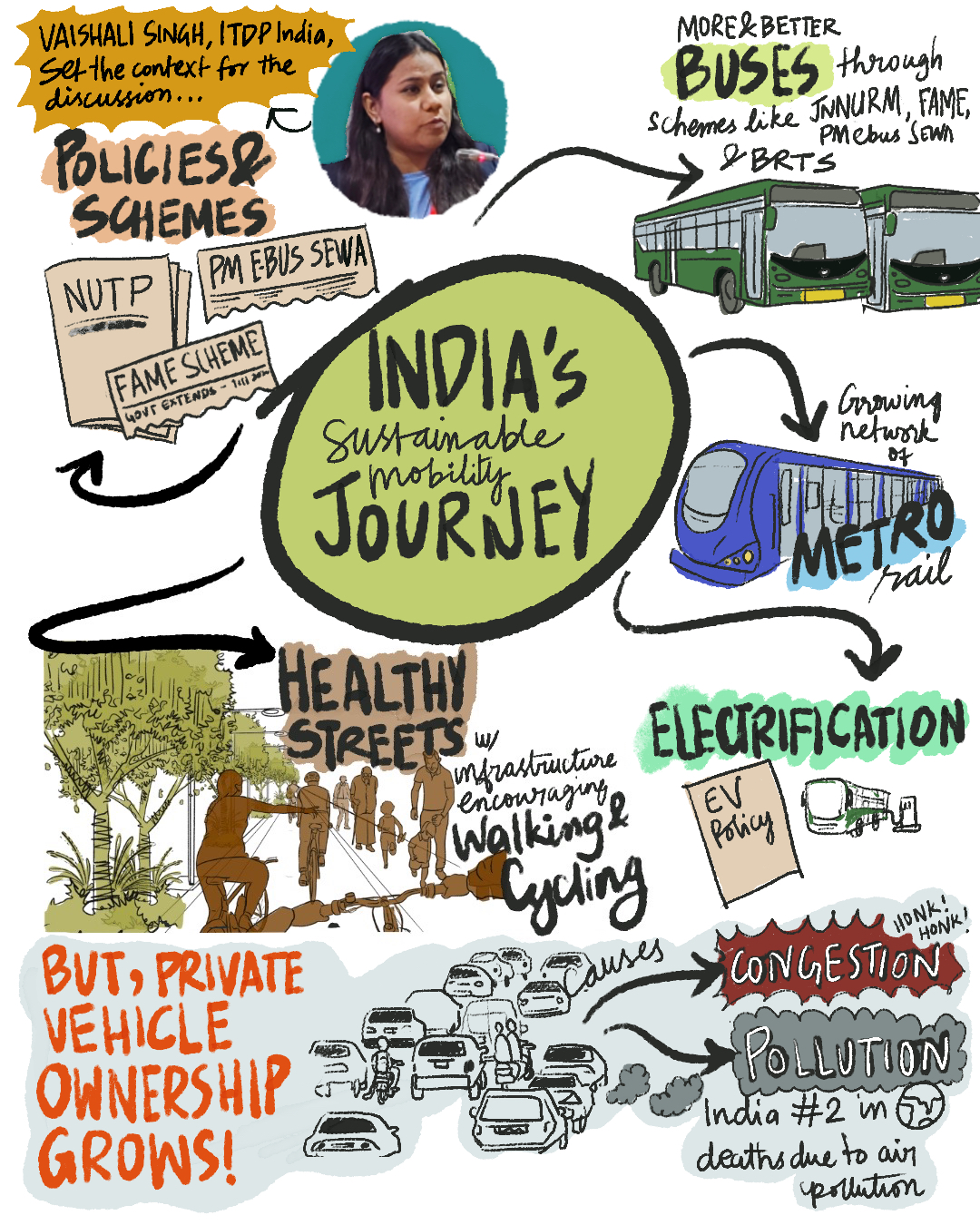

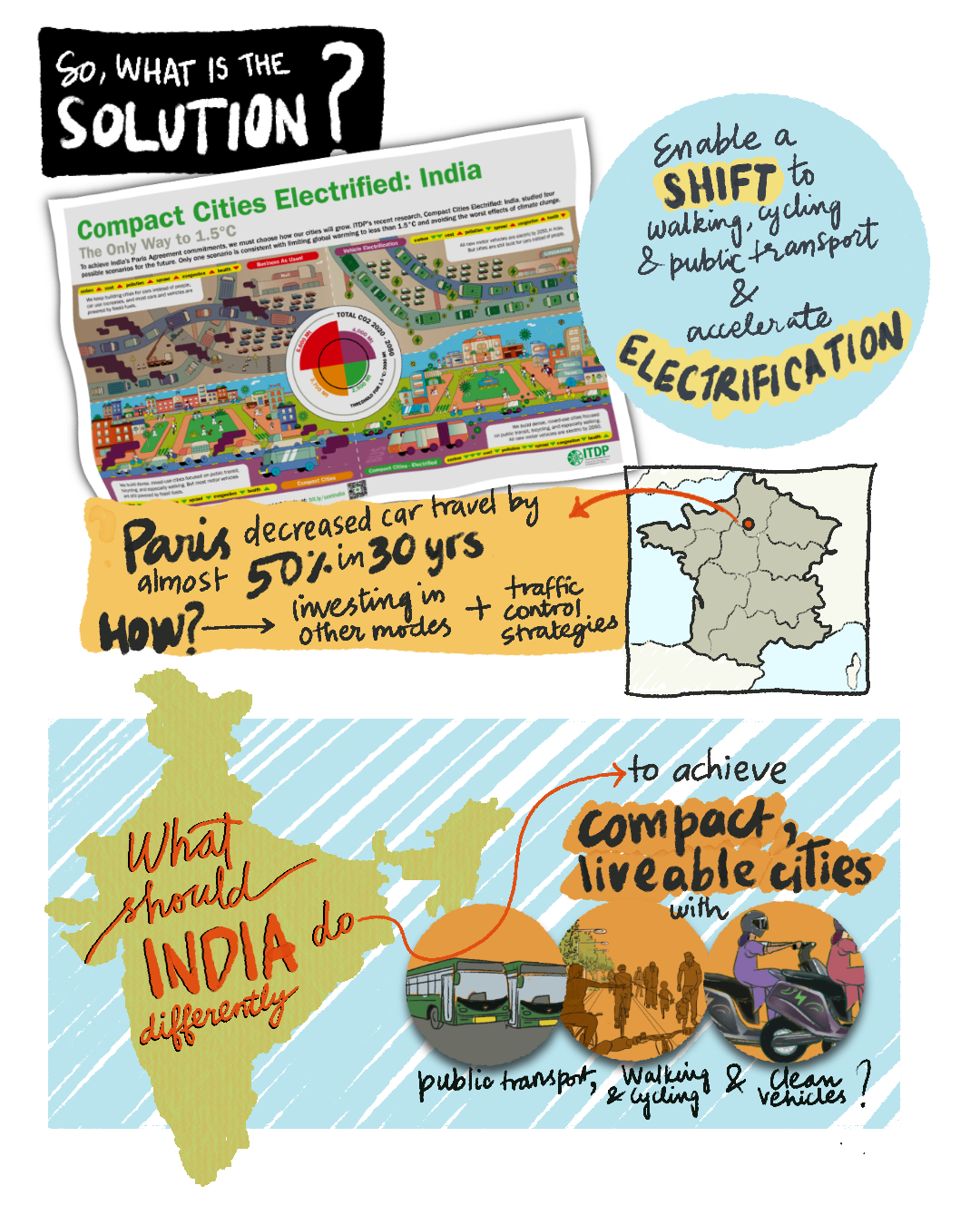

We’re happy to have hosted a roundtable discussion on ‘Compact Cities: Pathways towards India’s Sustainable Mobility Future’ at the 16th Urban Mobility India 2023 Conference, organised by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs and the Institute of Urban Transport (India).

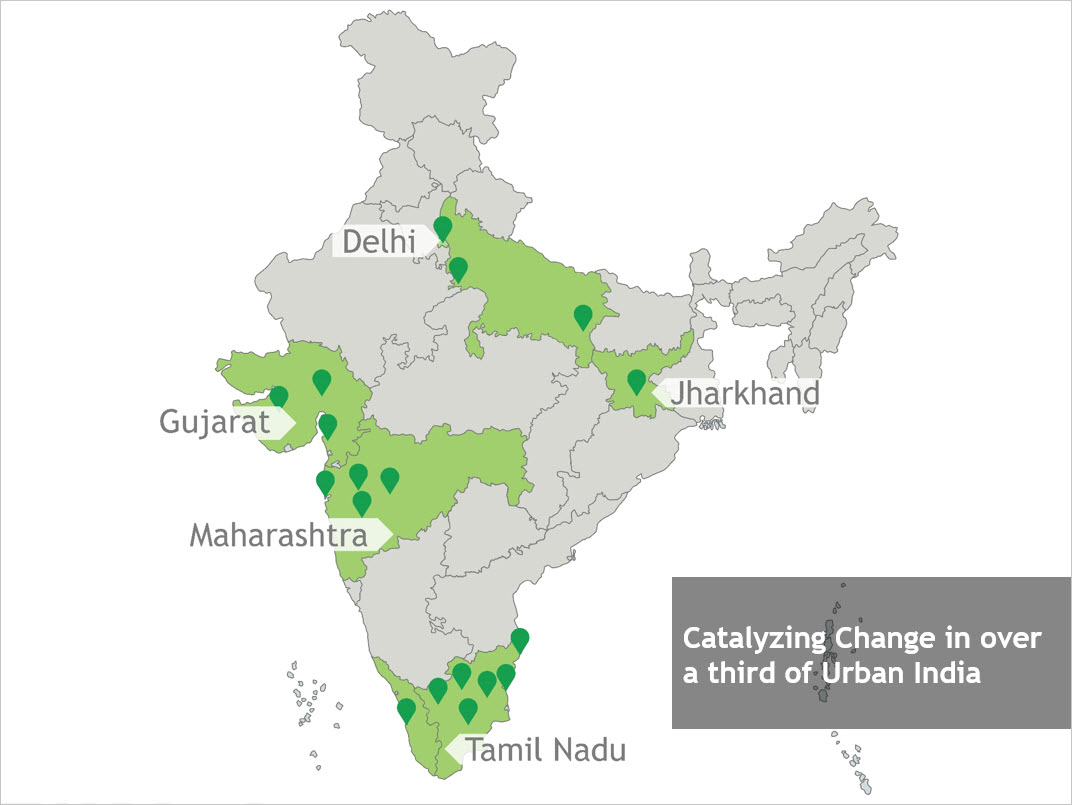

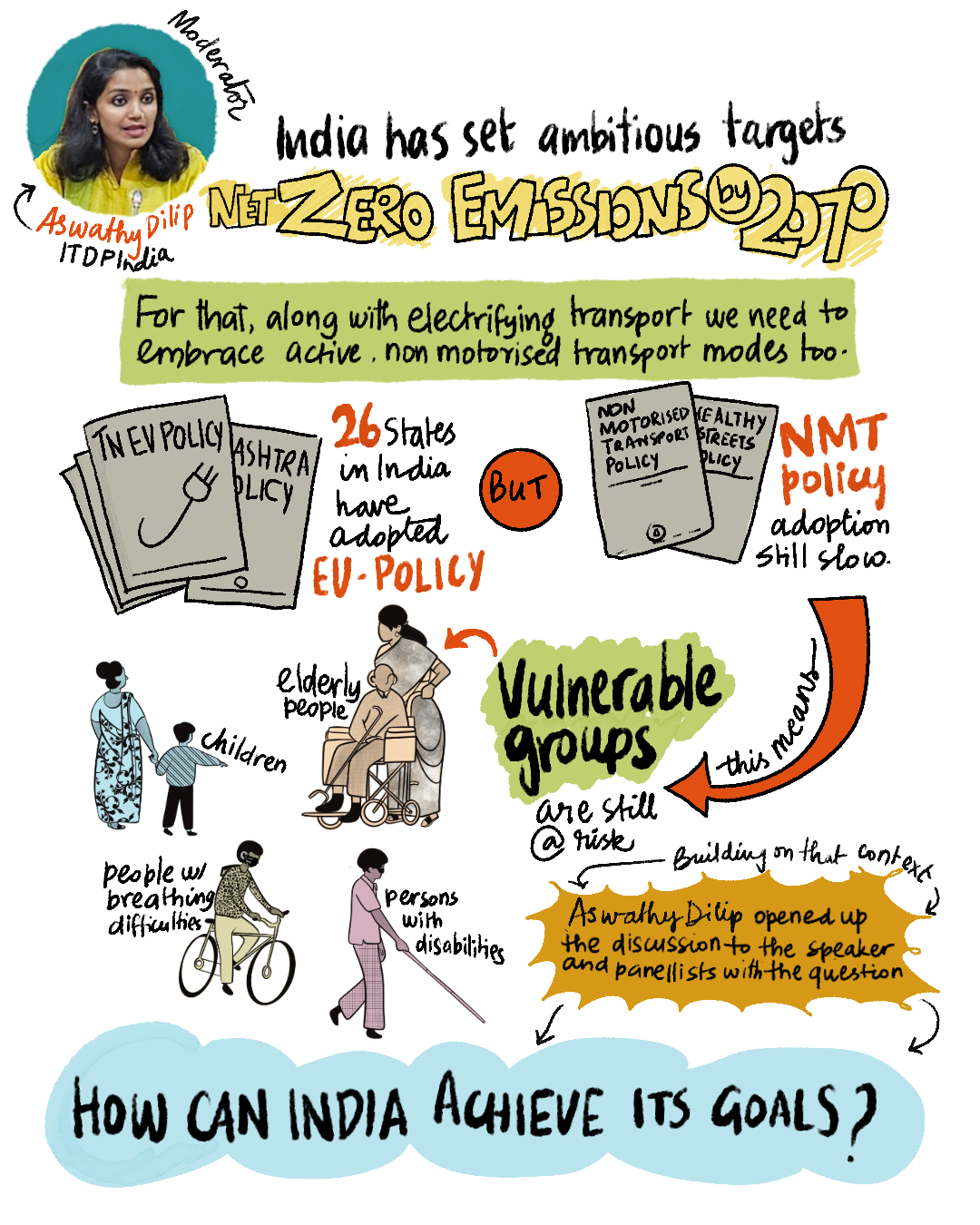

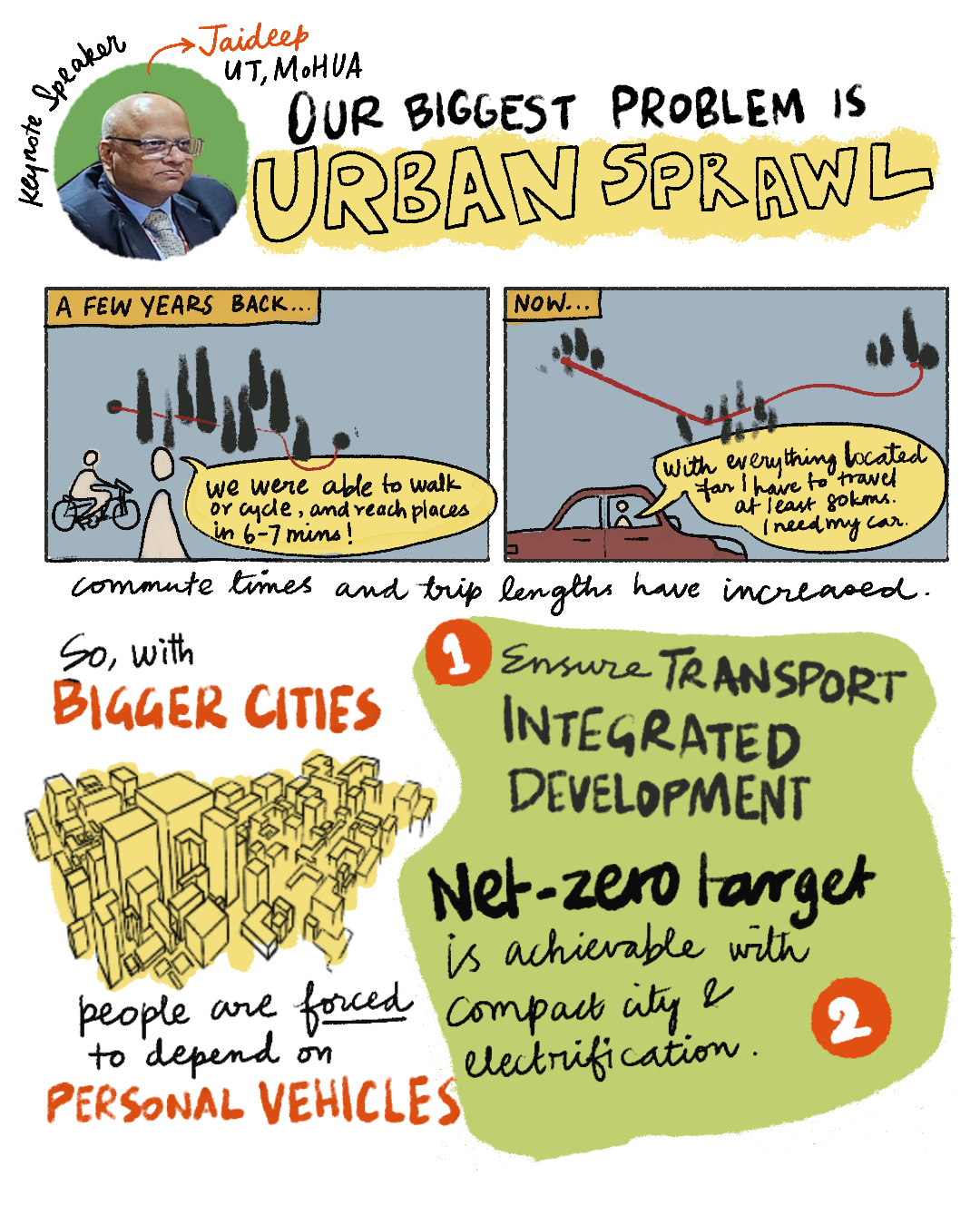

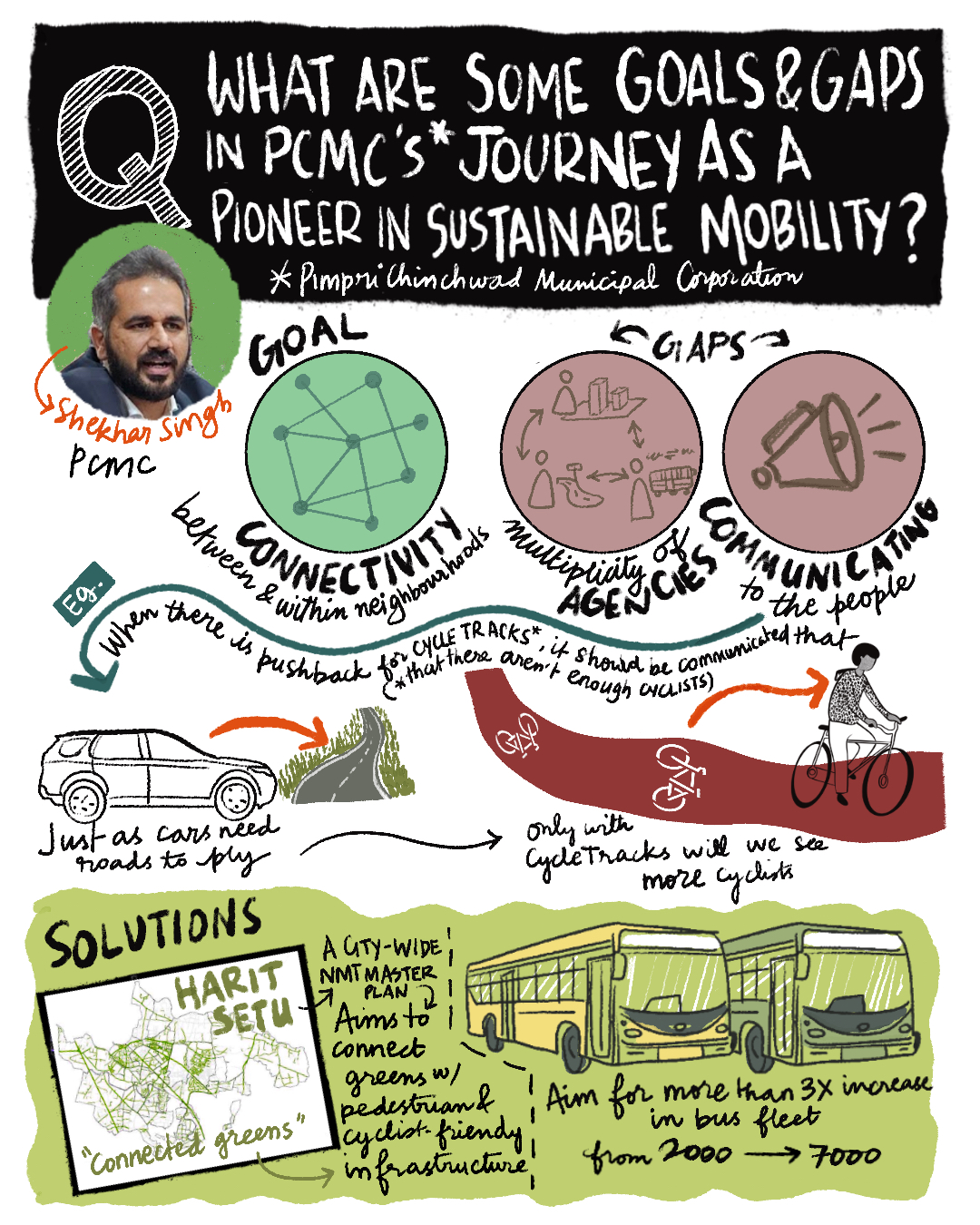

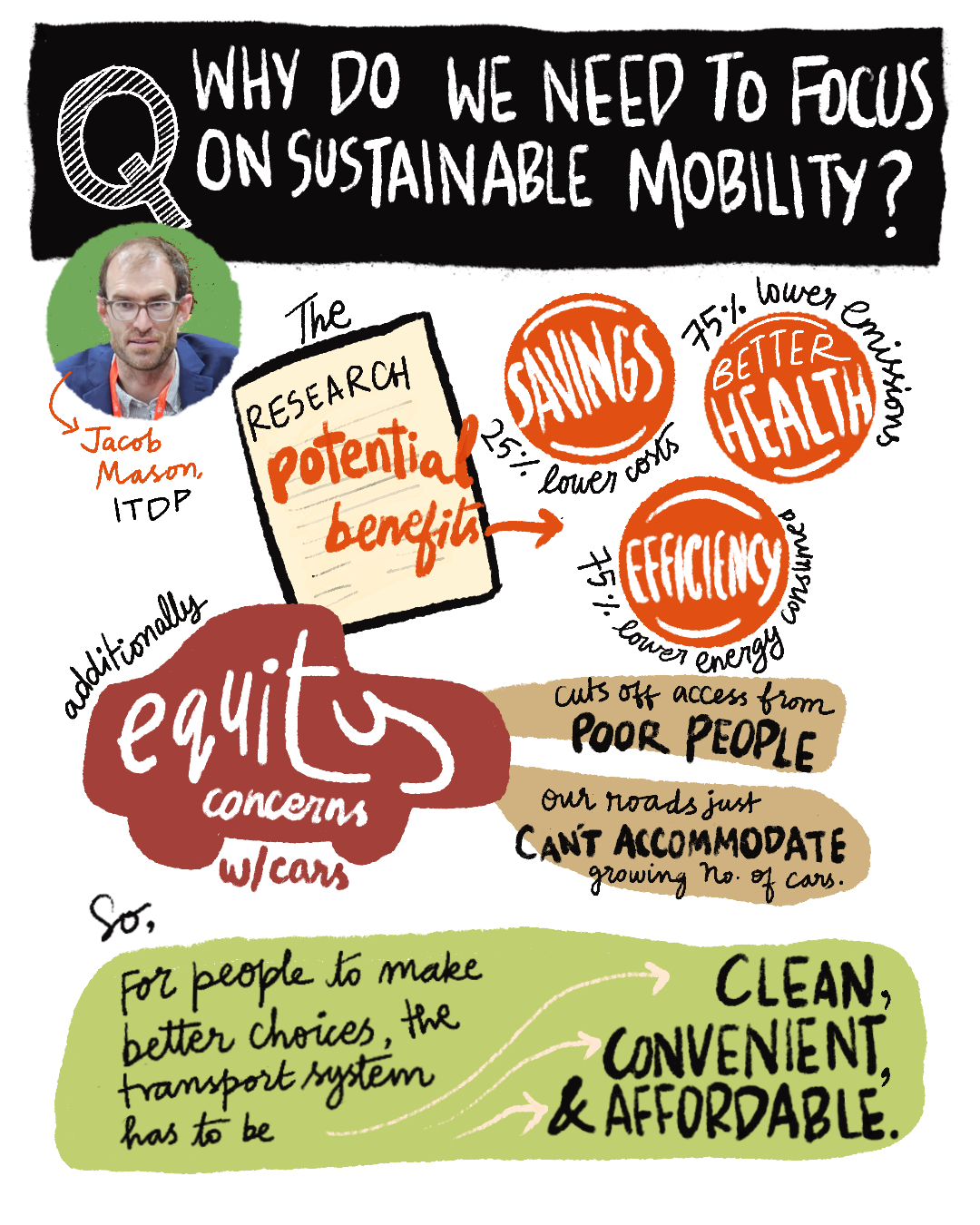

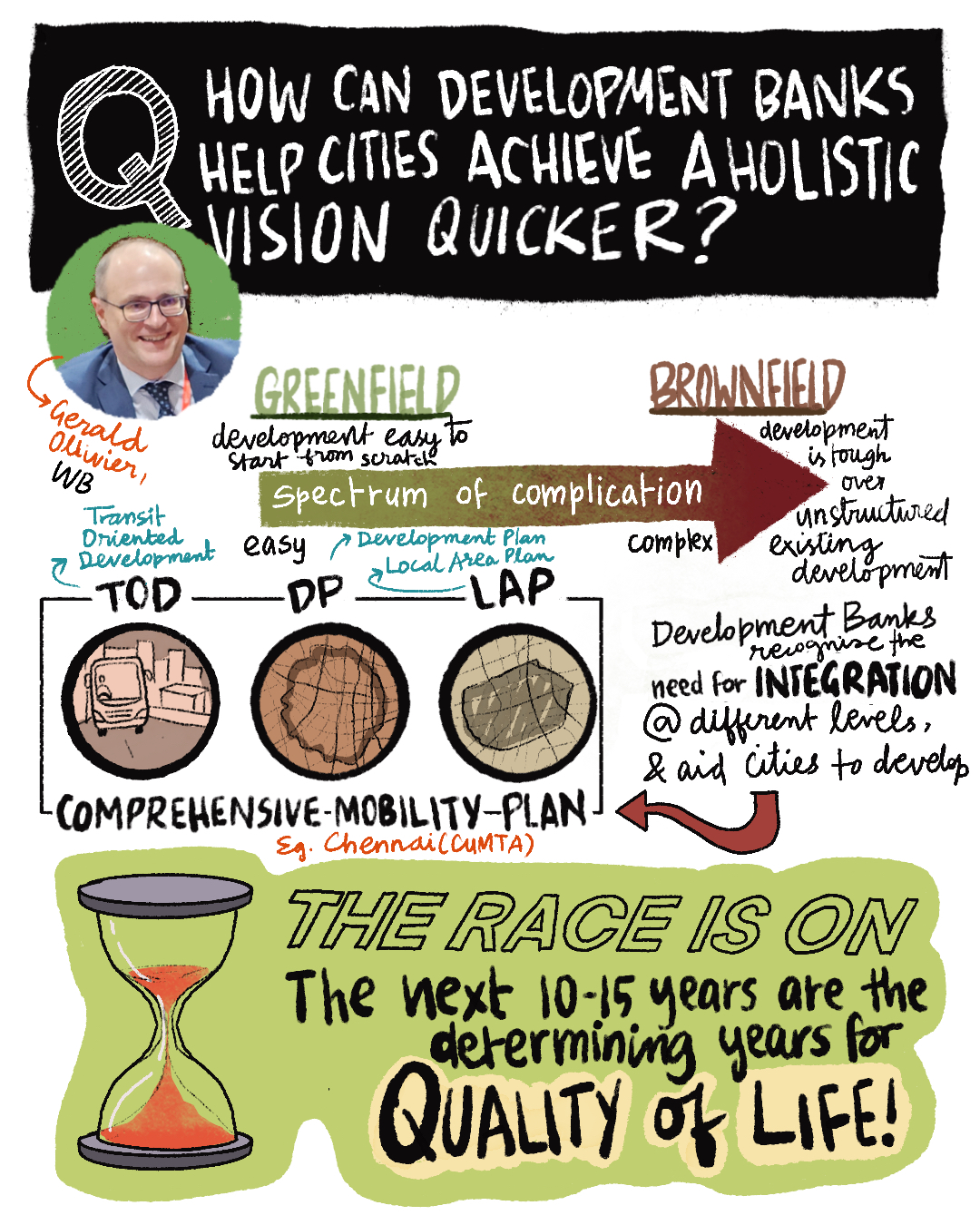

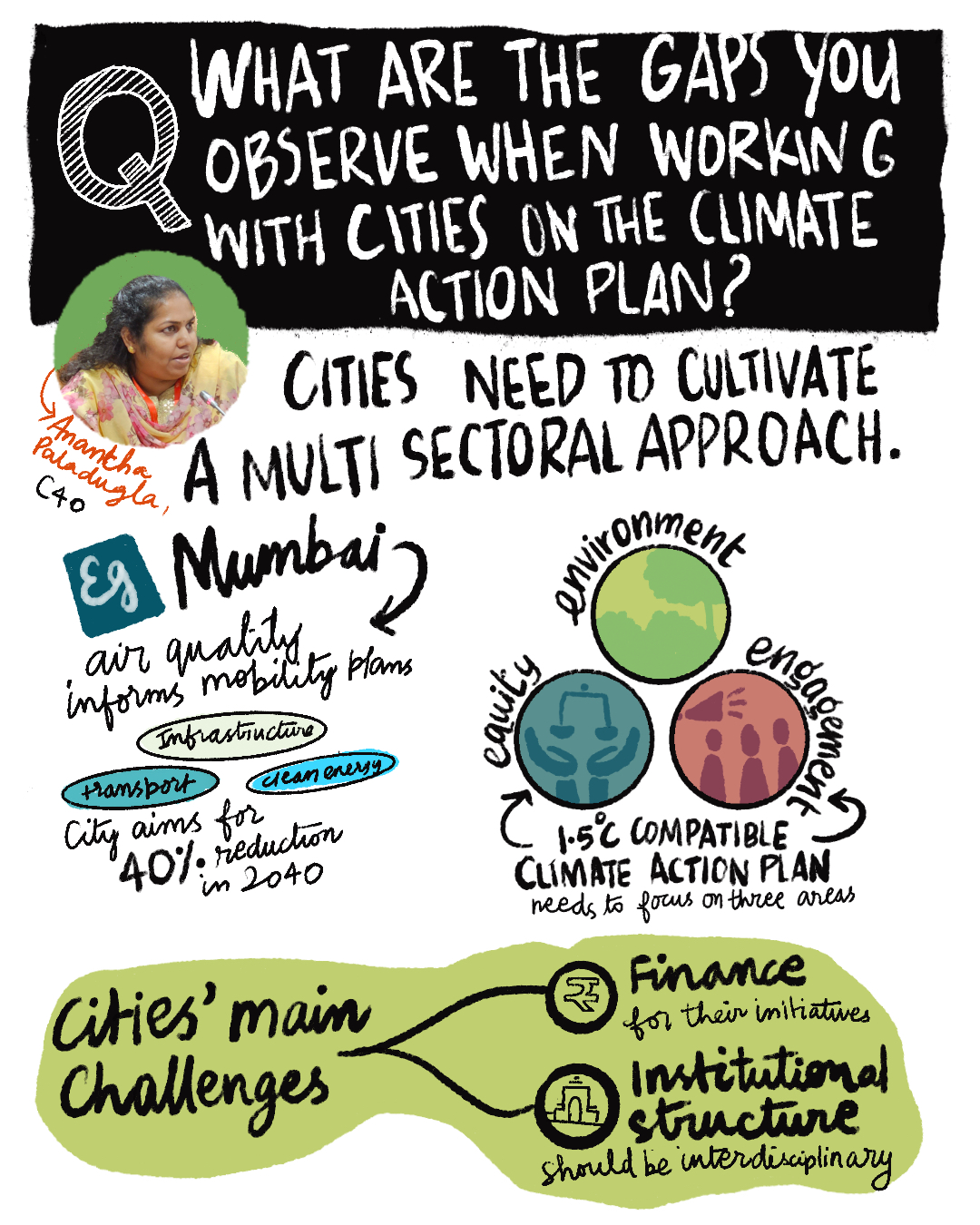

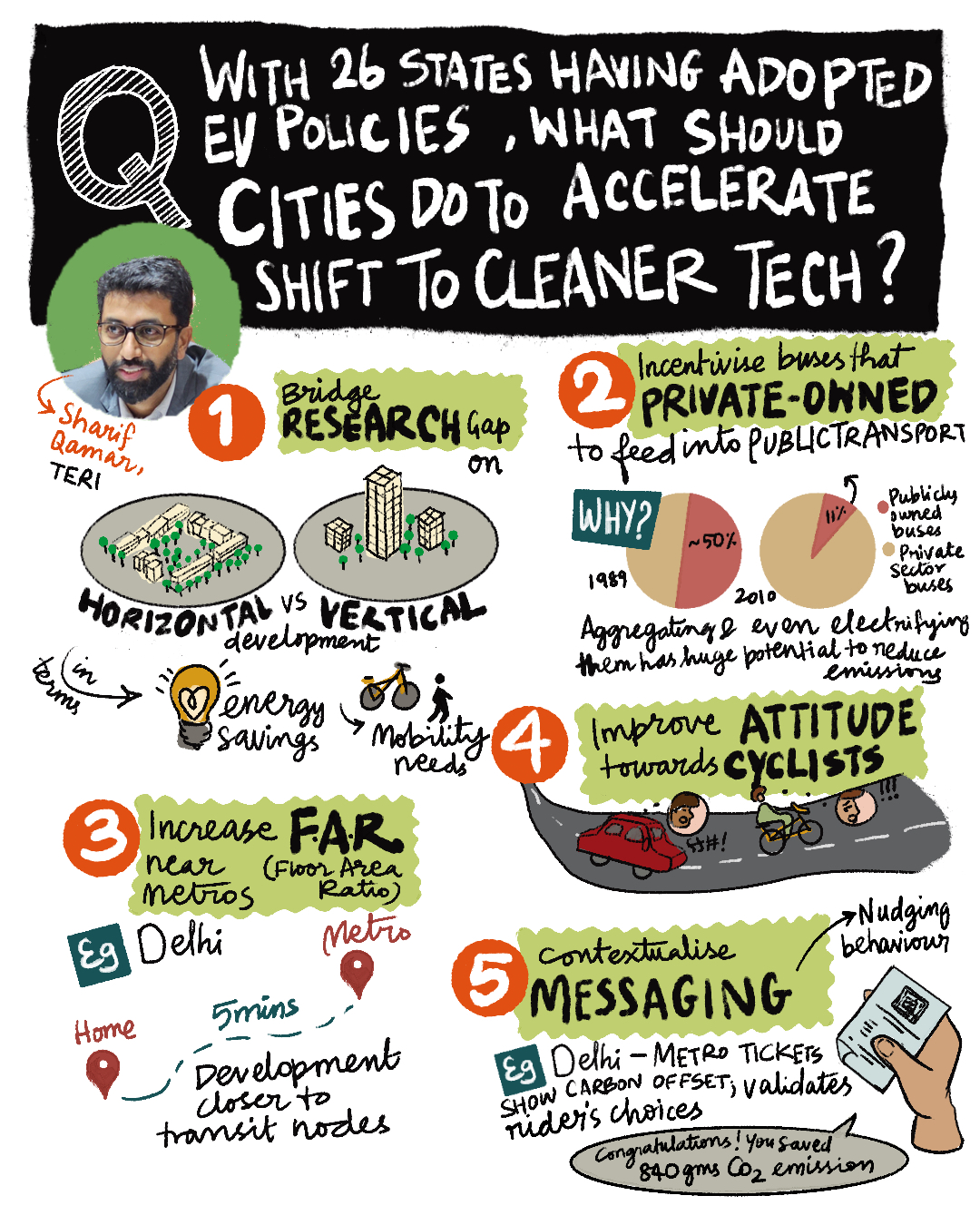

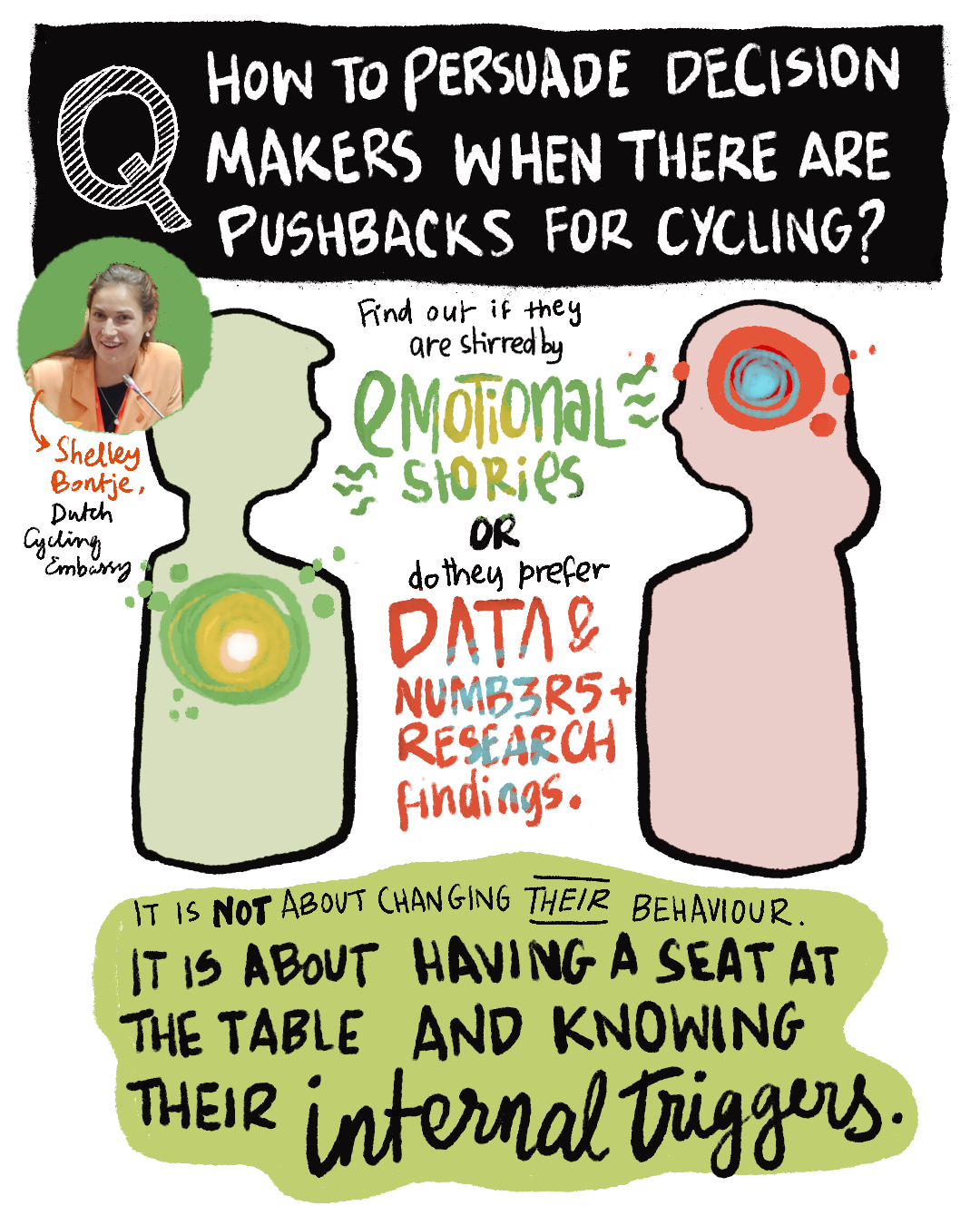

Moderated by Aswathy Dilip, Managing Director, ITDP India, the roundtable sparked an insightful conversation with key decision-makers and experts who stressed the importance of fostering collaboration between various departments to adopt a comprehensive and interdisciplinary strategy aimed at developing cities that are compact, electrified, and sustainable.

Check out this infographic blog for a detailed overview of the session and the main insights from the speakers:

Conceptualized and Designed by Varsha Jeyapandi

With Inputs from Keshav Suryanarayanan

Consultation with Nashik Municipal Corporation

Consultation with Nashik Municipal Corporation