A case for improving Delhi’s last-mile connectivity

Delhi—yeh sheher nahi, mehfil hai— a nostalgia bestowed upon Delhiites, from savouring the aromas of gully food, to being enchanted by the mehfil on old streets, and sometimes combined with a feeling of impending chaos. What happens when this chaos threatens the very existence of Delhi’s mehfil? Are we ready for ‘yeh Delhi sheher nahi, parking garage hai’?

As difficult it may be to let go of the age-old nostalgia of streets imagined as mehfils (gathering spaces for sharing poetry or classical music), the reality is that Delhi is clogged with cars! This is despite the city operating India’s “best-run mass rapid transit system” – the Delhi Metro. It’s vast network of over 340 kms helps 26 lakh people commute every day in the National Capital Region (NCR). While the system is classified as one of the largest in the world, it caters to less than 10 percent of NCR. Personal motor vehicles continue to rule the roost.

On the other hand, Delhi’s bus system is completely omitted from the public transport equation. Based on the existing demand and the burgeoning population, Delhi is short of over 6,000 buses – which means, Delhi needs to double its existing fleet strength. Efforts to bridge the gap in the supply of buses is the need of the hour. Lack of efficient public transport systems and the absence of last-mile connectivity has fuelled the insatious demand for personal motor vehicles. Let us now look at the issue of ‘last-mile’ connectivity.

Last-mile connectivity—how people actually get to and from the stations, particularly the Metro—has been a matter of concern among Delhi commuters. Issues surrounding the safety, convenience, and comfort to reach a station from a workplace or home, and vice-versa, has been the talk of the town for a few years now, yet neglected.

Privately run CNG autos, e-rickshaws, Gramin Sewa, and the Phat Phat Sewa have stepped in to provide last-mile connectivity, in the interim. While these systems have the stamp of legality by the State government and have managed to satisfy a portion of the mobility demand, they are largely unorganised and unregulated. The debate of whether they are a resource or a nuisance, continues.

Delhi is reported to have one lakh e-rickshaws, of which a mere 35,000 are registered, and over a lakh CNG autos. Filling the last-mile connectivity gap comes at a cost of traffic snarls and safety concerns among its citizens. Areas around metro stations have become the new choke points given the lack of integration with formal public transport, haphazard parking on main roads, and an overall lack of traffic and parking management.

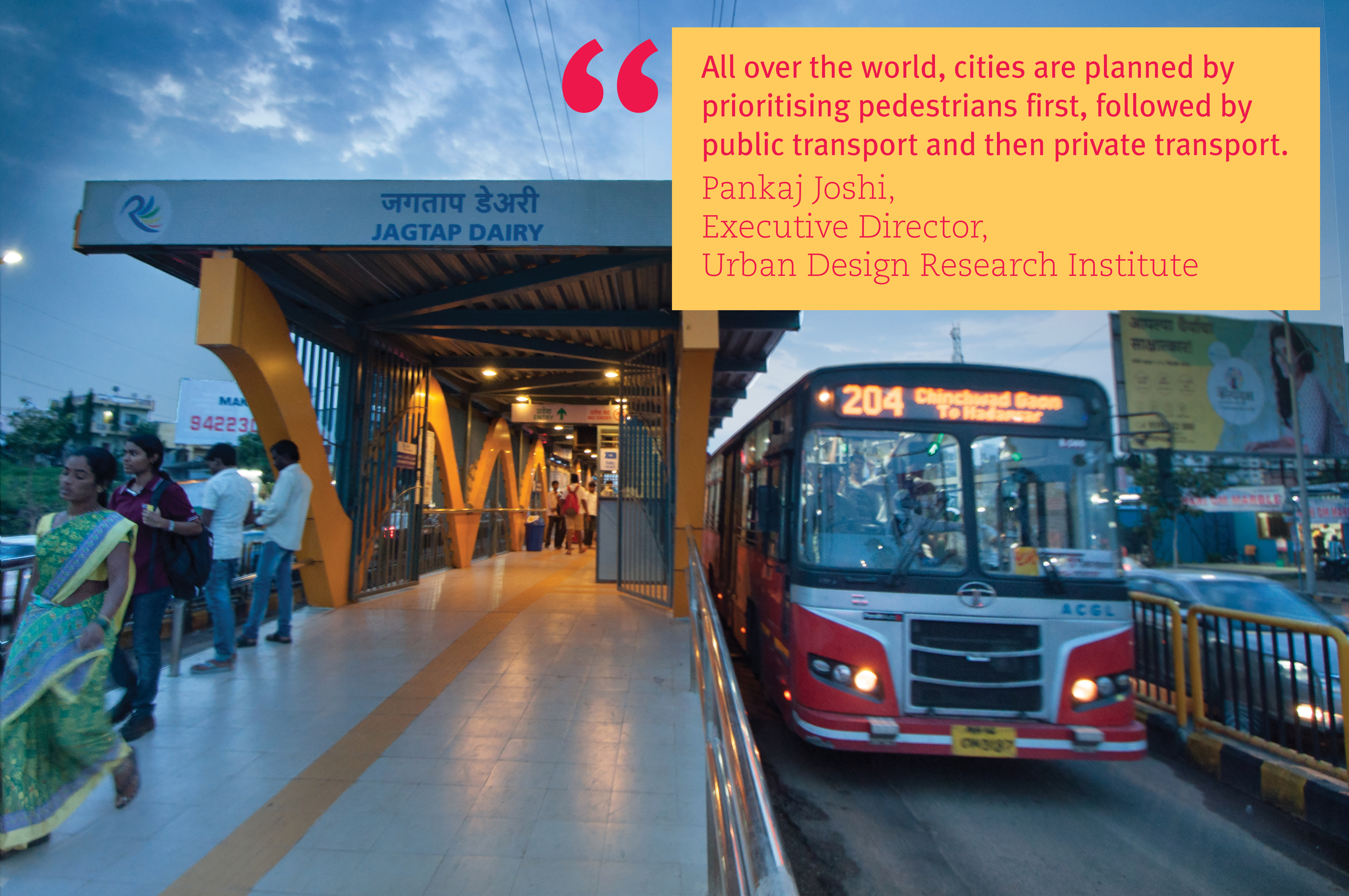

It may be time for Delhi to shift focus from its archaic approach to connect the dots of its public transit system – bring home the mini-bus. When it comes to bus-based transit, let’s face it, this underdog of transit is by far one of the most efficient, affordable, and convenient modes of transport. Just one mini-bus can replace five rickshaws, or in other words, the bus can move more people in fewer vehicles in a compact amount of road space.

The mini-bus can provide the best option to improve last-mile connectivity. With better technology, services, and integration with the metro, the bus can unclog streets in Delhi, especially those around metro stations. So what does that mean for rickshaw drivers – are their livelihoods at risk? A successful transition should ensure that rickshaw drivers are formally employed into the system.

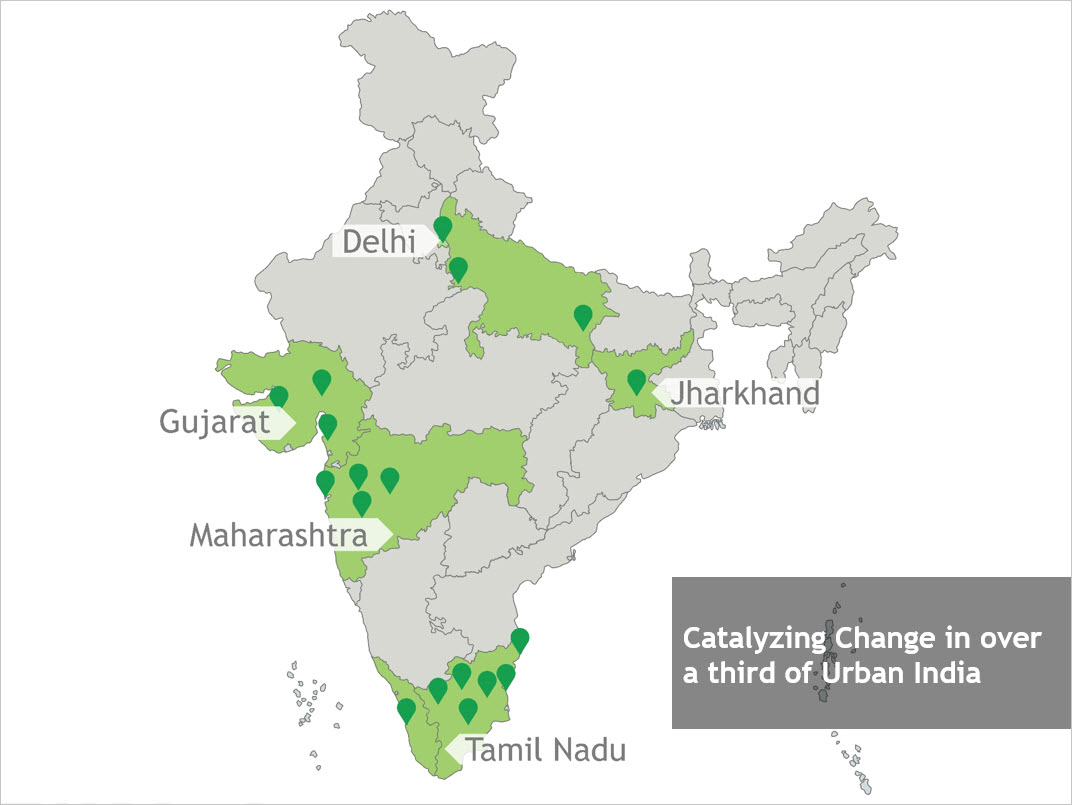

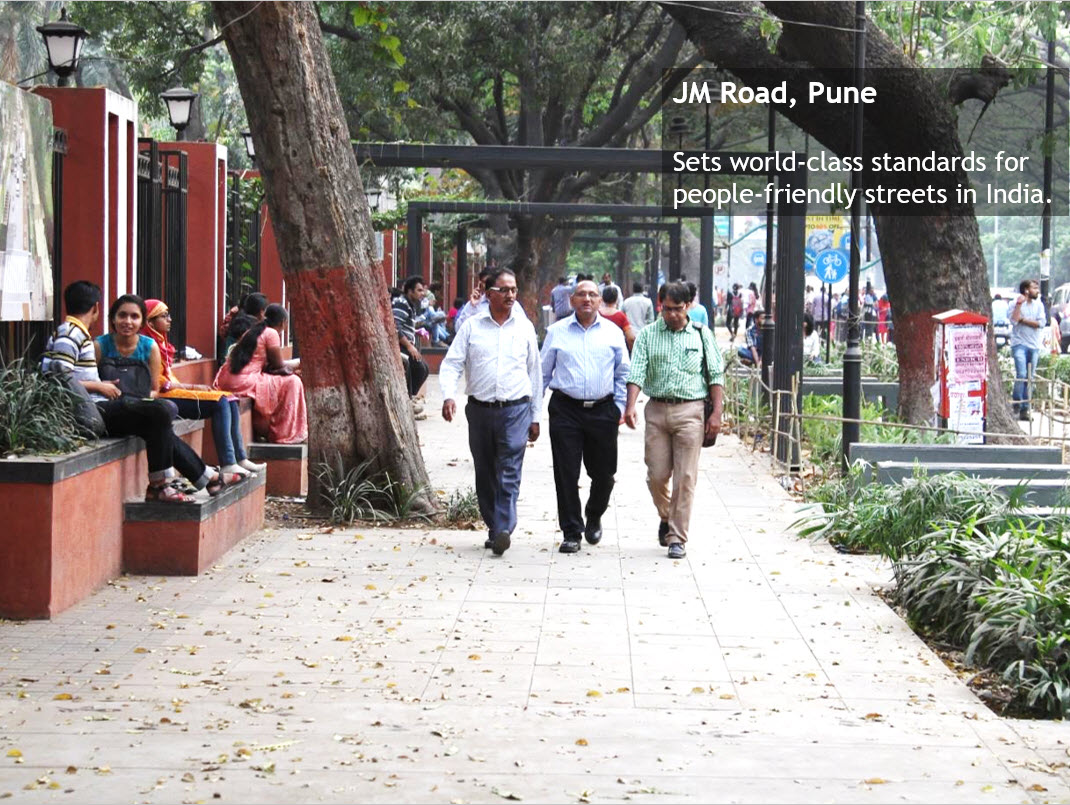

For Delhi to transition towards a people-friendly city rather than a personal motor vehicle garage, it needs to improve accessibility, affordability, and frequency of public transit as well. Cities like Pune have taken the initial steps of assessing public transit system gaps through the People Near Transit (PNT) tool, prepared with technical assistance from the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP) India programme. Pune has endorsed the PNT tool to further improve its public transit reach to reduce dependency on personal motor vehicles – a similar issue that Delhi has been tackling for over a decade. Delhi can use the PNT tool to reshape its public transport to serve maximum and pollute minimum.

For far too long, cities have ignored what is arguably the most affordable and flexible public transit option, the humble mini-bus. In the name of last-mile connectivity, rickshaws have filled the gap and where unavailable, cars have taken over. In the case of Delhi, where the city can no longer afford to squeeze more cars onto its roads, the bus can provide mobility to the maximum number of people in a compact amount of road space. Delhi should champion a publicly-run mini-bus system to solve its last-mile connectivity woe; after all, a successful bus-system has never failed to move a city.

Written by Kashmira Dubash

Technical Direction: Vishnu Mohanakumar