As published in Economic Times.

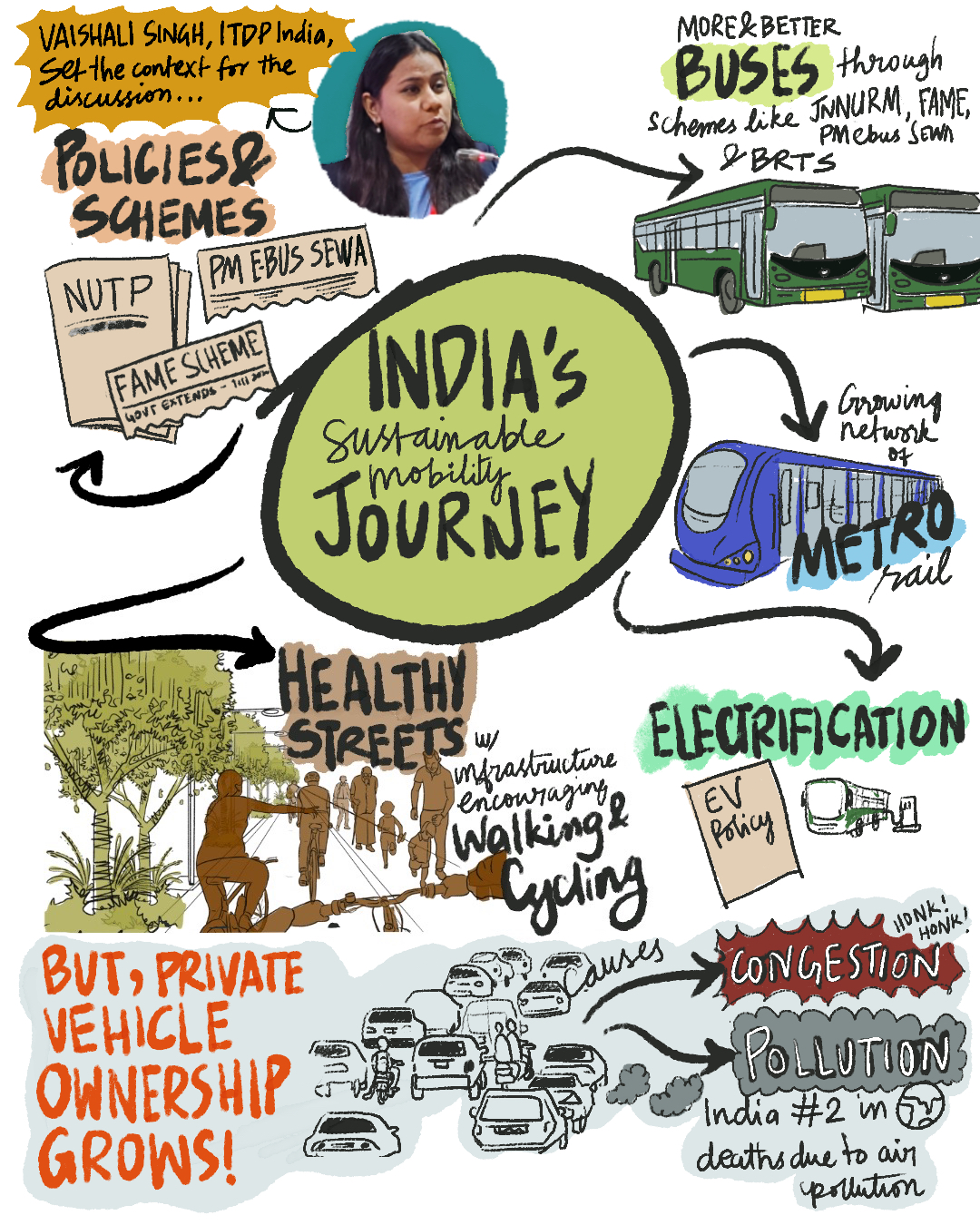

In the last decade, India has channelled substantial investments to power the electrification of our go-to means of transport—the humble bus. The bus is a crucial player in our race against the climate crisis. We have 1.4 lakh publicly owned and operated buses in India. Even if just one-fifth of these buses go electric, it could reduce 6 lakh tonnes of CO2 per year. This sparks hope.

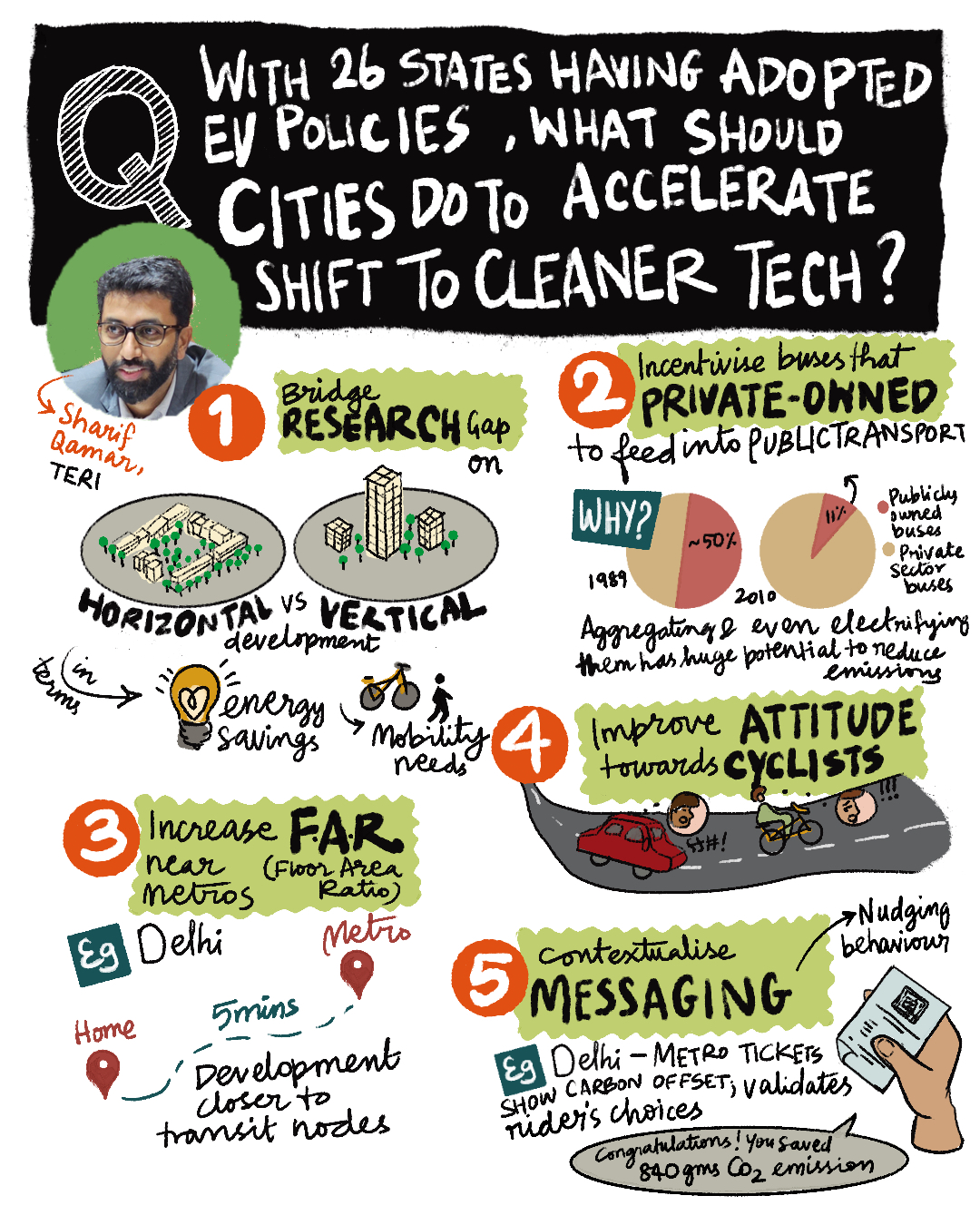

India’s response through its schemes such as FAME I and II, and the PM e-Bus Sewa Schemes targets incentivising the public bus sector. But this strategy inadvertently overlooks a critical stakeholder—private sector bus operators. Why are they critical? The bus ecosystem in India has about 20 lakh buses with two vital players: public buses often take centre stage, but another is the private sector, which owns and operates a whopping 93% of buses in India.

Leaving the private sector out of national schemes and incentives is like playing a sport with less than 10% of the team—how can we hope to win the match against climate change without their contribution? Let’s see how we can bring them in.

The current ecosystem—starting the game at a disadvantage

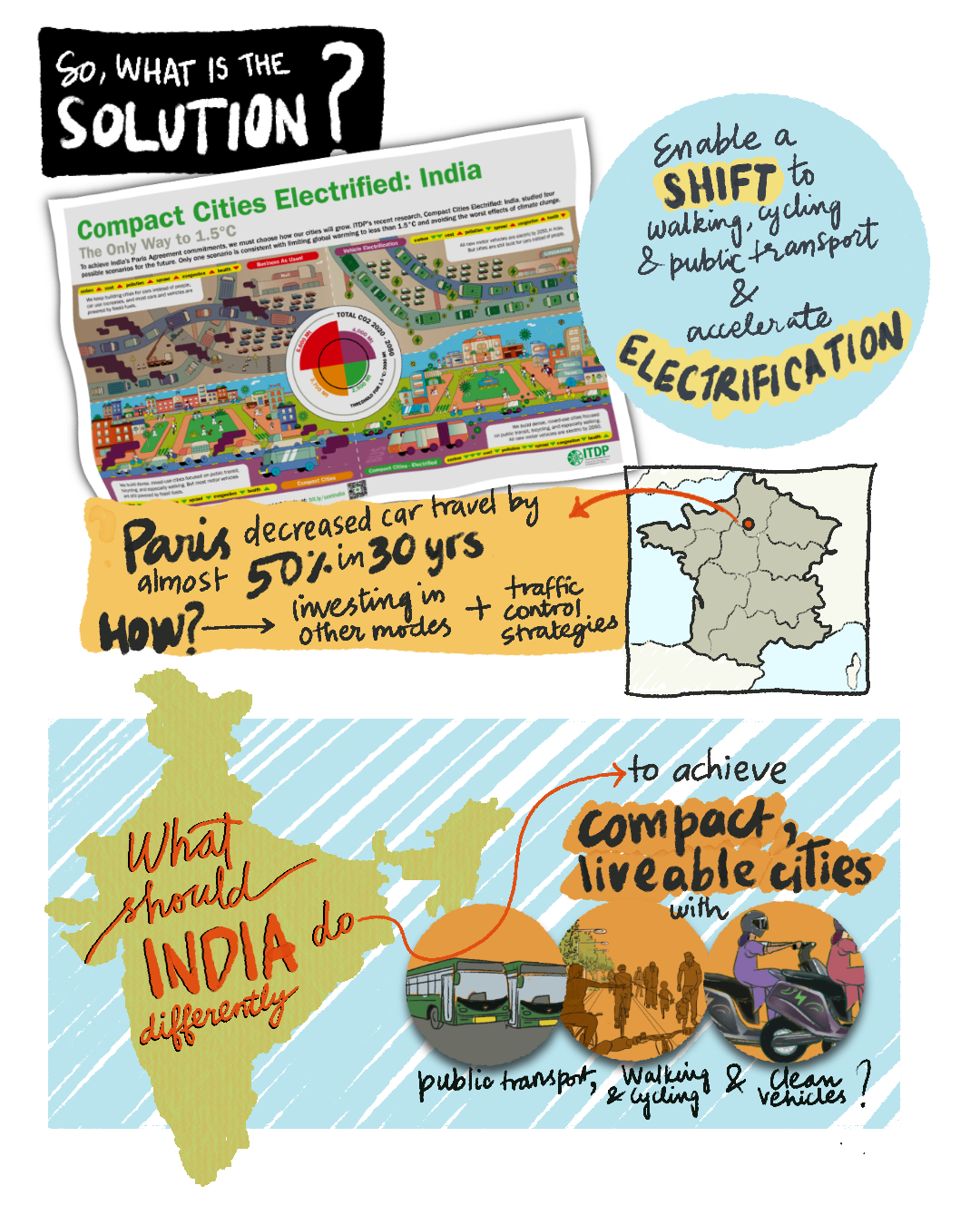

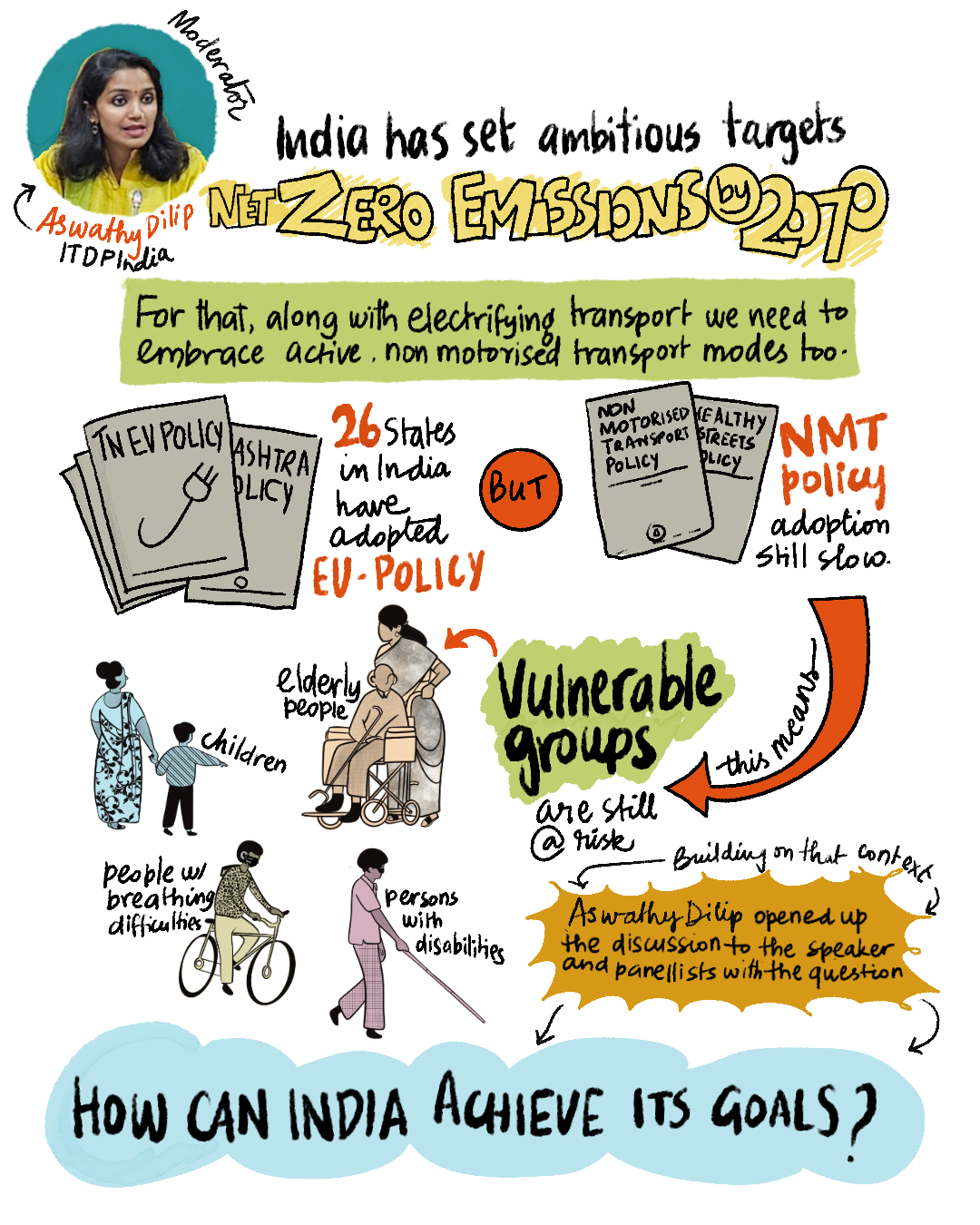

At the national level, India has set a target of 40% of new buses being electric by 2030, and introduced schemes to incentivise the procurement of e-buses. Schemes such as FAME I and II sanctioned 5595 e-buses to date, just for the public sector. The 2023 announcement of the Rs 57,613 crore PM-eBus Sewa scheme, targeting the public sector to deploy 10,000 e-buses, focuses on improving urban connectivity, particularly in cities lacking organised bus services. Yet, it neglects the involvement of the private bus sector, who tend to be the primary service providers in these cities.

Even with these Schemes, the uptake of e-buses has been gradual in the public sector. This limitation stems from the financial instability and hesitancy to fully embrace electric buses, primarily due to concerns about insufficient grid capacity. With just 7,000 e-buses on the ground, we have a long way to go to meet the national target and the bus demand.

By 2030, the projected demand for stage-carriage non-urban buses is 7 lakhs, while the demand for urban buses is anticipated to reach 3 lakhs. Private sector buses can help fill this gap to some extent, but we still need an overall increase in bus fleets—both public and private—to meet this demand. As we look to increase these fleets, we have an opportunity to accelerate a transition to cleaner electric buses. But without any strategies and mechanisms for the private sector, we’re on the field, but we may be starting the match at a disadvantage.

Rethinking strategy to level up the playing field

Just as a coach strategically positions players on the field to seize scoring opportunities, the government must orchestrate a winning game plan by creating favourable conditions and incentives for private sector buses to transition to electric. There are multiple ways of levelling the playing field, but let’s focus on two interventions at the national level: Financial mechanisms and regulatory support to reduce upfront costs of purchasing an e-bus; Zero Emission Vehicle (ZEV) mandates to achieve economies of scale and boost the supply of e-buses.

The primary factor contributing to the private sector’s hesitancy in transitioning is the substantial up-front cost of procuring an e-bus. An electric bus costs four times as much as a diesel bus. In conversation, private operators said they would need to be within 1.5 to 2 times the cost of diesel buses to be feasible to invest. For this to happen, it is important to loop in financing institutions—banks and non-banking finance corporations (NBFCs)—to offer loans to private bus operators based on their creditworthiness, with favourable terms such as low-interest rates (4-6%), extended repayment periods (from six-eight years), and no additional collateral against the loan except for the electric bus.

Another avenue worth exploring with financing institutions is a model of leasing buses. Under this arrangement, financers can lease them, providing coverage for insurance, maintenance, and battery replacement, for at least nine years to be financially viable. Private bus operators would then be responsible for covering staff, permits, and energy costs. Furthermore, state governments should consider legalising permits to facilitate lease models where ownership and operations can be separate.

While these incentives are designed to stimulate demand for e-buses by reducing the financial barriers with their procurement, it may not be enough unless regulatory goals and a ZEV mandate are part of the plan at the national level—this can guide a winning strategy. In 2023, e-buses accounted for only about 5% of the total sales of buses. The national target is to get to 40% by 2030. A ZEV mandate can help boost this by requiring original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) to produce and sell a minimum number of ZEVs as a percentage of their total sales each year. Such a mandate would not only encourage OEMs to prioritise and produce electric buses but also play a crucial role in reducing the cost of e-buses.

If OEMs begin to manufacture more, the production cost per e-bus reduces due to economies of scale. It also allows OEMs to negotiate better prices for components and batteries, ultimately benefiting the end user. As mentioned earlier, the private sector accounts for a larger portion of the market than public buses. Demonstrating a high demand can incentivise OEMs to increase their product more aggressively, aligning with the long-term goals of the ZEV mandate.

We can learn from an example like California, which has pioneered implementing ZEV mandates, setting ambitious targets for automakers to produce and sell electric vehicles, leading to a potential 100% ZEV mandate by 2035. Since 1990, California’s ZEV program has aimed to reduce local air pollution and transition from internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles to electric, starting with a 2% ZEV sales mandate. Despite initial hurdles, technological advancements and policy revisions, including the 2012 alignment with national greenhouse gas standards, have paved the way for a substantial rise in new EV sales, reaching 12.4% in 2021. California now anticipates achieving 100% by 2035, reflecting its commitment to addressing climate concerns and meeting net-zero targets.

In it to win it – our match against climate change

In our race against climate change, electrifying public buses is a critical game plan, but obstacles in the form of financial struggles for STUs have slowed our momentum even with the Centre’s support. It’s time to add another tactic for the private sector, an untapped powerhouse waiting to deliver. Extending financial incentives such as lower interest rates for loans, longer loan tenure, and a leasing model can address their biggest concern of costs related to e-buses. But to guide a winning strategy, regulations such as ZEV mandates are required at the national level to increase the supply of affordable electric buses.

As the final whistle blows, the message echoes loud and clear: the only championship-winning move towards faster electrification of buses is to put together a strong team that combines the public and the private sector.

Written by Kashmira Dubash – Sr Programme Manager, Communications and Development, Sivasubramaniam Jayaraman – National Lead: Transport Systems and E-mobility

With technical inputs from Vaishali Singh – Programme Manager, E-mobility and Public Transport Systems

Edited by Keshav Suryanarayanan – Deputy Manager, Communications and Development